Response to the 2024 document: “Gynaecology and Maternity Hospital Services in Liverpool – Case for Change”

Contributors Sheila Altés (Lead author), Felicity Dowling, Greg Dropkin, Rebecca Smythe.Thanks to Jim Hollinshead and Dave Pedder for their input.Published by Save Liverpool Women’s Hospital Campaign C/O News from Nowhere 96, Bold Street Liverpool L1 4HY

(Postal address only)

email savelwh@outlook.com

INTRODUCTION

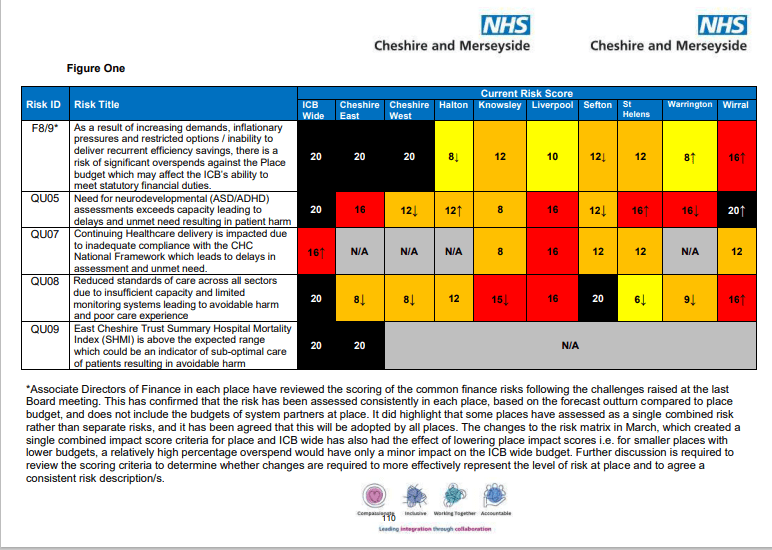

The Women’s Hospital Services in Liverpool (WHSIL) programme was set up by NHS Cheshire and Merseyside Integrated Care Board (ICB) in January 2024, following a review of the way clinical services were organised across the Liverpool area (Liverpool Clinical Services Review January 2023). Its primary purpose was to: “Develop a clinically sustainable model of care for hospital-based maternity and gynaecology services that are delivered in Liverpool”

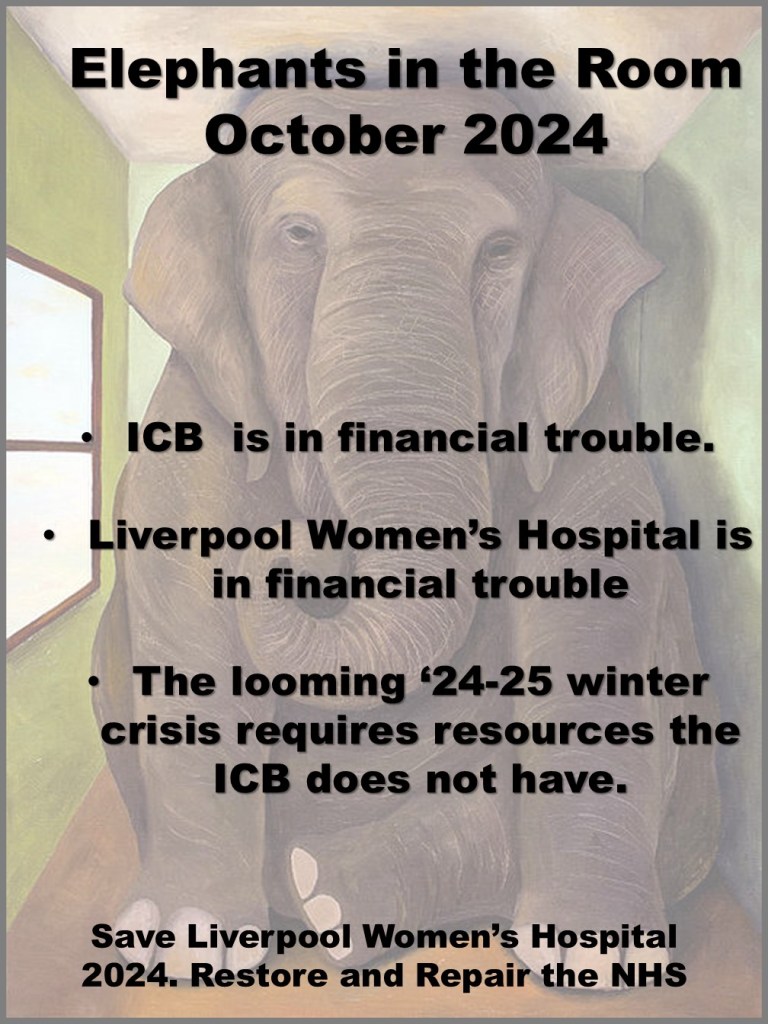

They concluded that the way hospital-based maternity and gynaecology services are currently organised did not provide women with the best possible care and experience. At a clinical engagement event in May 2024, a Clinical Reference Group was formed to review an earlier case for change. On the 9th of October 2024, this review was then presented to the ICB for approval at an Extraordinary Board Meeting – Women’s Services in Liverpool. The threat to re-locate Liverpool Women’s Hospital (LWH) surfaced once again.

BACKGROUND

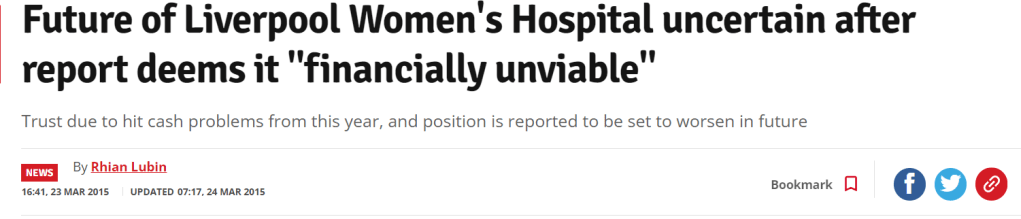

Discussions to close LWH at its present site on Crown Street and re-locate to a smaller new building adjacent to one of the general hospitals in Liverpool began in 2015.

The emergence of austerity as the driving political ideology and with cutbacks in funding for the NHS meant that the Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group (LCCG) had to close one of its hospitals. The Women’s Hospital, although less than 20 years old at the time and being massively underfunded, became a candidate. The then Chair of the LCCG announced, on a BBC Panorama programme, that Liverpool had too many hospitals and one had to close. The following day it was published in the Liverpool Echo that the chosen hospital was the Women’s Hospital (15 March 2015).

At that time the Five Year Forward View (later re-launched as the Long Term Plan) was published and the Naylor Review was commissioned.

Briefly, the Five Year Forward View was to make efficiency savings (cuts) by moving some hospital services to community care, which was deemed cheaper. Bed closures ensued and secondary care capacity reduced. However, resources were not invested into the community and social care services; this resulted in waiting lists for elective surgery increasing and longer stays in hospital for patients waiting for social care placements. Following the Health and Social Care Act (2012), the number of contracts awarded to private providers increased and lucrative contracts were awarded to private hospitals to carry out NHS-funded procedures in an attempt to bring down the waiting list (The King’s Fund 2021). This was a situation beneficial to private hospitals. They cherry-picked the most low risk uncomplicated procedures, leaving the more complex cases to the NHS. If complications occurred the NHS provided a safety net, as any patient needing critical care was transferred to an NHS facility. Compensation claims were also left for the NHS to pick up as they had outsourced the care to a private provider (Centre for Health and Public Interest 2014), The COVID pandemic exacerbated the waiting lists, this has led to an increase in the private health care insurance industry and an increase in patients paying for their own health care (British Medical Association 2024). But that was always the plan.

The Naylor Review, published in 2017, outlined how profits could be made from selling off NHS land and buildings. Its findings were in line with the requirements set out in the Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) which were introduced in December 2015, to fast forward NHS England’s Five Year Forward View. Eventually, STPs evolved into what we have today, an Integrated Care System managed by an Integrated Care Board (ICB). This is a statutory body responsible for planning and funding NHS services over a large area. In this instance, the area is Cheshire and Merseyside, one of 42 such areas.

The Naylor Review, however, could only sell NHS land or close NHS buildings if there was a clinical reason for deeming them unsafe and “not fit for purpose”. And so began the construction of a clinical case for change at the Women’s and to re-locate it from its valuable Crown Street site.

The LCCG put forward several clinical arguments to strengthen their evidence for re-locating LWH:

- Lack of adult critical care on–site

- Patient transfers between hospitals

- Inability to support women with complex health needs

- Inadequate space for current neonatal facility

- Unavailability of haematology/pathology services.

They then published a Pre-Consultation Business Case (PCBC, 2017) that set out several options for the re-location of LWH. Their preferred option was to build a new hospital at the site of the new Royal Hospital, and, connected to the new Royal by a link bridge. The plans were presented to the North West Clinical Senate for review. They declared it a suboptimal solution and only viable as a short-term solution because it was not co-located with children’s services. However, the Carillion debacle, and subsequent delay in completing the new Royal Hospital, the COVID pandemic, underfunding and reorganising of the NHS, and public opposition, forced these plans to be shelved until recently.

CLINICAL CASE FOR CHANGE 2024

There have been many improvements to enhance the quality of women’s hospital services in Liverpool. Many of these correspond to suggestions set out in The Alternative Clinical Case printed by Save Liverpool Women’s Hospital Campaign (Save Liverpool Women’s Hospital Campaign/Keep Our NHS Public Merseyside, 2017). Transfers between hospitals have been greatly reduced following the construction of a Community Diagnostic Centre. CT scans and MRI scans can now be carried out on-site. Plans to establish a 24/7 Blood Transfusion laboratory at the Women’s are underway, working in conjunction with Liverpool Clinical Laboratories. The care of pregnant women with complex needs is planned at many of the outpatient clinics at LWH. They are seen by a consultant obstetrician and a consultant of the relevant specialism to plan their care. A medical emergency team is being recruited. Joint multidisciplinary teams manage gynaecology patients with complex needs and there are joint operating lists on both the LWH and the Royal Hospital sites. A £10,000,000 development of gynaecology day cases is currently underway at the Crown Street site.

The neonatal unit has been refurbished and extended to the cost of £15,000,000+. The hospital also has a new, state-of-the-art fetal medicine unit. Despite these and many other improvements at LWH, the ICB is intent on relocating LWH. Their Case for Change has identified 5 clinical risks which it states need to be resolved.

CLINICAL RISKS IDENTIFIED IN THE CASE FOR CHANGE

RISK 01

Acutely deteriorating women cannot be managed on site at Crown Street reliably which has resulted in adverse consequences and harm.

They state: This risk is caused by a lack of a range of services and specialist staff e.g. critical care, medical and surgical specialties, 24/7 blood transfusion labs.

Potential impacts include untimely transfers to other sites, delays to care and treatment, poorer outcomes, patient harm and death.

At present there is not an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) available at Crown Street, there is a high dependency unit (HDU) and staff working on the gynaecology HDU have undertaken training for critical care (LWH 2024a). The Cheshire and Merseyside Critical Care Network (CMCCN) has stated that providing an ICU at LWH would not meet national standards due to the “geographical and specialist nature of LWH”. At the public engagement meeting held on 20th November 2024 a member of the ICB agreed that an ICU at the Crown Street site would not be sustainable due to “low levels of activity”. In other words, so few women have needed intensive care that an ICU would not be feasible.

The Case for Change argues that LWH needs to be at the same site as an Intensive Care Unit. In the Case for Change review, they reference:

- National standards for emergency care

- Current clinical guidelines and recommendations

- Core standards for Intensive Care Units.

They conclude that these recommendations state maternity and gynaecology need to be on the same site as an ICU. This is gross misrepresentation of these guidelines, they do not state that. The Core Standards for Intensive Care Units (2013) state that it is preferable to have an intensive care unit on site but units without such provision must have an arrangement with a nominated level 3 CCU and an agreed protocol for the stabilisation and safe transfer of patients to this unit when required. The RLUH is the nominated level 3 unit for LWH as part of local critical care arrangements and is situated approximately 1 mile away. The South East Clinical Senate’s recommendations are not mandatory. So, this ICB argument for moving LWH off the Crown Street site is un-evidenced. The Case for Change argument on this point is not supported by the South East Clinical Senate or by the Intensive Care Society (2013,2022).

ICB papers of the 9th October 2024 (page 7) state that 69 women were transferred from LWH needing critical care over a 4-year period, this equates to less than 2 patients a month. No comparative data was presented concerning adult transfers from other hospitals. The COVID pandemic occurred within that period, which no doubt affected these statistics. LWH is the recognised provider of high-risk maternity care and complex gynaecology procedures in Cheshire and Merseyside. It is inevitable that emergencies will occur and that transfer to a CCU will be needed. If services were moved to RLUH or the Aintree site women needing critical care would still be transferred, intra-hospital transfers need the same procedures as inter-hospital transfers. The women’s hospital in Birmingham is co-located with the acute hospital site and women needing critical care have to be transferred by ambulance. Inter-hospital transfers of critically ill adults happen frequently. NHS England data from the 2019/2020 year demonstrated that there were between 20,000 and 25,000 adult critical care transfers performed and the numbers may be higher (Adult Critical Care Transfer Service 2024).

ACUTELY DETERIORATING WOMEN

It has been noted that, sick pregnant or recently pregnant woman can present to health professionals in any location; emergency departments, walk-in centres, medical or surgical wards or in the community and general practice. Enhanced Maternal Care Guidelines were published in 2018. They summarise recommendations for the care of pregnant or recently pregnant women who become acutely or chronically ill. They state that early recognition and management is essential and a system to do so to be in place. The Maternity Early Observation Warning System (MEOWS) is a system that is used by clinicians at LWH to alert them to any deterioration. According to LWH website (LWH 2024b) there is a broad range of services for enhanced maternal care at LWH. They include: enhanced midwives, a perinatal mental health team and specialist antenatal clinics. A Medical Emergency Care Team is being recruited to enable optimal care and transfers if necessary. A 24/7 on site consultant obstetrician is planned. The Women’s has been selected as a Maternal Medicine Centre (MMC), one of 3 in the North West. This will provide regional care for safer outcomes and better birth experiences (Liverpool Women’s Maternal Health Centre July 2022 (LWH 2024b)).

The ICB has focused on a minority of women who have needed to transfer to ICU but have failed to take into account the 50,000-plus patients who use services at LWH each year

RISK 02

When presenting at other acute sites (e.g. A&E), being taken to other acute sites by ambulance or being treated for conditions unrelated to their pregnancy or gynaecological conditions on other sites, they do not receive the holistic care they need.

They state that there is a lack of women’s services and specialist staff at other sites in Liverpool. They go on to say that the potential impacts are the same as for risk 1 i.e. untimely transfer to other sites, delays to care and treatment, poorer outcomes and death.

It is difficult to see how relocation would solve this. If LWH were re-located to the RLUH, women are still likely to turn up at the Aintree site and vice versa. Is the ICB envisaging maternity and gynaecology services at both sites? Neither the Royal nor Aintree provide all services on-site. This dispersal of services would not fit with the ethos of a specialist hospital for women and that would be a gender inequality as women’s health differs from that of men in many unique ways. It is influenced, not just by biology but also conditions such as poverty, employment and family responsibilities. Women’s reproductive and sexual health has a distinct difference compared with men’s health. Cardiovascular disease, common to men and women, can lead to pre-eclampsia in a pregnant woman. Sexually transmitted infections can cause such outcomes as stillbirth or neonatal death. There is a long history of women with health issues being misdiagnosed or dismissed by doctors (Dusenbery 2018). Breathlessness and chest pain are often labelled as anxiety and not a symptom of heart disease (Hatherley 2022). Severe pain, heavy bleeding and irregular cycles are often dismissed as “just having a period” and that women should just “put up with it” (Wellbeing of Women 2024). This could lead to women receiving poor treatment and misdiagnosis (Cleghorn 2021) A study by Manchester Metropolitan University (2024) found that health care providers poorly understood endometriosis, the study found that it takes an average of 7.5 years to get a diagnosis of endometriosis. There is a lack of research in how medication can affect women, they are more likely to have side effects as the outcomes of clinical trials usually focus on men as the default patient (Modi, N 2022). Female cells respond differently from male cells and hormonal changes in women can affect how drugs are metabolised, yet women are often marginalised in clinical trials (Sundari 2020). Other issues impacting on women’s health include unplanned pregnancy, non-consensual sexual activity, domestic violence and female genital mutilation.

These issues are well known to the specialist staff at LWH. At the meeting held on the 9th October, it was pointed out by a member of the public that if relocation of the Women’s took place, to no matter which site, there would only be one A&E department at that site and pregnant women and women with gynaecological problems would be taken there. He also pointed out that the Board’s own data state that 120 pregnant women attended the emergency department at either the Royal or Aintree site. This does not necessarily mean that they were transferred from the Women’s. It means that an emergency situation occurred while these women, who happened to be pregnant, were going about their everyday business, so of course they went to the nearest emergency department. This would happen no matter where the Women’s was located. The situation at the Royal A&E department in particular, is dire, with long waiting times and corridor care, whereas, at the Crown Street site there is a designated Emergency Department (ED) with clinicians who have a better understanding of women’s health than those at a general A&E department and much shorter waiting times. LWH provides an outreach midwife service to support pregnant women who are at other trusts in the city.

The majority of these women will have booked their ante-natal or post-natal care at LWH. The table on page 86 of the Board papers shows that in 2023 they supported a total of 35 patients. Conversations with medical staff at Royal Liverpool Hospital state that if a pregnant woman presents there and they have concerns, they immediately consult with the outreach team and if a midwife is needed they present promptly.

The data included in the clinical case for change report (NHS Cheshire and Merseyside Integrated Care Board, 2024) that in a 4 year period (2018-2022) there were 19 serious clinical incidents in gynaecology and maternity. Isolation from other hospital services was cited as a major causal factor but not a root cause. These are still very small numbers and do not take into account the effect of the COVID pandemic. Further data state that 148 clinical incidents, not individual patients (our edit), occurred in a 21 month period and were caused in full or in part by the Women’s being on an “isolated site”. They do not give any indication of their outcomes.

The figures showing the number of critical care transfers on page 55 of the Case for Change (lbid.) show that in 2018 there were only 8 transfers and 12 in 2022, the highest figures occurred between 2019 and 2021, during the Covid pandemic. Data presented on page 84 of the case for change show that over the last 6 years, 39 patients were transferred to RLUH from LWH that were defined by ambulance services as category 1, and there were 31 transfers to LWH from RLUH in the same category. Category 1 is a life-threatening, time-critical event needing immediate intervention. In category 2, defined as emergency, needing either on-site intervention or urgent transport there were 558 and category 3 which is an urgent problem but not life-threatening, there were 90. While some of these figures may sound alarming, they were over a 6 year period including a global pandemic, and compared with the estimated 25,000 transfers of critically ill adults annually in the UK, they are in reality very small numbers. The categories cited are relevant to the ambulance service. Critical care is not the same as emergency care. The main difference is that emergency care focuses on treating life-threatening injuries and medical conditions needing immediate treatment at the scene. Critical care focuses on the very ill patients needing round-the-clock attention from a specialised team of health professionals. Patients needing transfer from LWH to a critical care unit are stabilised before transfer. There are protocols in place to optimise the safe transfer of women and babies. Ambulance transfers between Aintree and LWH; there were 10 in category 1, 42 in category 2 and none in category 3, a total of 52. This was over a 6-year period.

In view of the evidence that women are marginalised in healthcare, it is ludicrous that the ICB is considering re-locating a hospital dedicated to women’s reproductive health to an acute general hospital where they are less likely to receive specialist care.

RISK 03

Failure to meet service specifications and clinical quality standards in the medium term could result in a loss of some women’s services from Liverpool.

They state that this risk is caused by an inability to meet key clinical co-dependencies due to lack of co-location of women’s hospital services with other adult hospital services.

The risk would disproportionately impact women and families from more deprived backgrounds who may not have the resources to travel outside the area.

All service specifications could not be met by co-location with either the Royal or Aintree. As the Board papers state, both acute sites cannot meet clinical standards and specifications either (page 88). Even if women’s services were to be re-located at both sites, specifications and co-dependencies would not be met as women’s and children’s services would not be co-located. This is unlikely to happen, given the considerable financial investment in the new RLUH and Alder Hey Children’s Hospital.

No hospital can provide for every eventuality. The Board papers state that some women have to travel to Manchester for their treatment. This implies that the treatment they need is not available at the acute sites in Liverpool, how will re-locating LWH change this? People are transferred out of their area for more specialised treatment every day. Certain procedures for some cancers are only available at the Christie Hospital in Manchester, ECMO( extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) is only available at 5 centres in the UK, cyber knife radiotherapy is available for NHS patients at 3 centres, and thrombectomies at 24 centres. Using transfers for complex procedures as an excuse for re-locating LWH is unreasonable.

LWH is a centre of excellence specialising in the health of women and babies, not only in Merseyside but in the wider North West region, parts of North Wales and the Isle of Man. It is the largest single-site maternity hospital in the UK and staffed by dedicated teams specialising in, obstetrics, gynaecology, anaesthesia, genetics, fertility, nursing and midwifery as well as researchers and educators. Many of these are internationally renowned consultants with a wide range of special interests including; hypertension, diabetes, maternal and fetal medicine, gynaecological oncology, pelvic floor surgery, palliative care, haematology, urogynaecology, polycystic ovarian syndrome and many more (LWH 2024c).

In March 2023, as part of the NHS commitment to halve the maternal mortality rate by 2025, specialist medical care centres for women during pregnancy were established. LWH, as a centre of excellence, was selected as one of 3 such centres in the North West, the other 2 being at Manchester Royal Infirmary and Royal Preston Hospital. The aim was for pregnant women with serious medical problems to have access to specialist treatment at these centres. In all there are 17 such centres across the country and networks linked to these centres will ensure that access to expert maternal medicine care is available to all women (LWH 2024b).

These centres will be able to provide treatment and procedures that are safe in pregnancy. Following an initial assessment, if their condition is well managed they will be given a management plan to continue at home with support from their local maternity team. The most serious cases will be closely monitored with specialist treatment by the centre. As well as all of these services, LWH is currently working towards being a designated provider of complex termination of pregnancy, endometriosis, placenta accreta and fetal therapies, in partnership with Alder Hey (Case for Change, page 87).

It is difficult to believe that services could be withdrawn from such a prestigious, regional centre of excellence that has been selected as a Maternal Medicine Centre. NHS England would have been aware of the configuration of services before its selection.

RISK 04

Recruitment and retention difficulties in key clinical specialities are exacerbated by the current configuration of adult and women’s services in Liverpool.

They state: this is caused by the inability to provide comprehensive onsite multi- disciplinary team (MDT) working and training on acute sites. MDT training and working is emphasised in current clinical practice, however this is hard to achieve in women’s hospital services in Liverpool. Roles in Liverpool may seem less attractive because of the current service configuration. Clinicians may feel exposed and/or unable to perform their duties without outside support from the wider MDT.

The potential impact of this risk is that vacancies may persist. Services could become increasingly fragile and difficult to deliver. There would be a negative impact on existing staff leading to increasing turnover and recruitment difficulties.

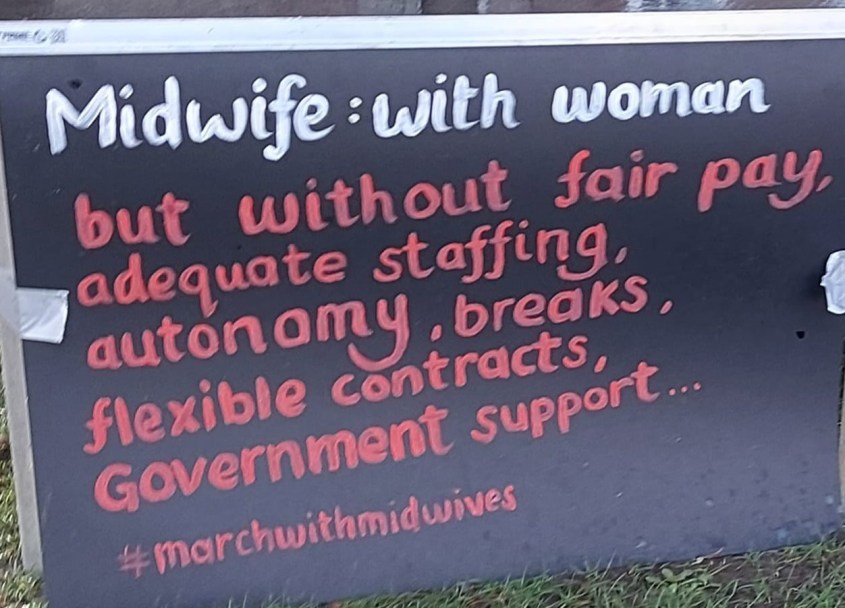

Recruitment and retention of staff is a national crisis in the NHS as a whole and not just in maternity services. The Royal College of Midwives estimates that there is a shortage of around 2,500 full-time midwives working in the NHS (January 2024).

A search of job vacancies at the Women’s in October 2024, showed a vacancy for one staff nurse on the Hewitt Suite and one midwife for fetal medicine and one genomic practitioner, the rest appeared to be administrative vacancies. At the Board meeting of 9th October 2024, we were assured that LWH had its full complement of midwives according to the calculations of Birthrate-Plus. This is a system to calculate the required number of midwives to meet the needs of women throughout pregnancy, labour and the post-natal period both in hospital and in the community setting. This system has been in place for a number of years and although some believe it to be reliable, others differ in opinion as there are no comparable studies of other methods (Griffiths et al 2024). At LWH there have been a number of newly qualified midwives recruited, and although there is a preceptorship pathway in place to support them, the reduction in older more experienced midwives, due to retirement, will have a negative effect on their development of skills and knowledge.

Board papers suggest that multidisciplinary team (MDT) training and working is not provided at the Women’s. This is untrue. There is a multidisciplinary team of specialists who meet regularly to plan the care of pregnant women with complex needs. Now that the Women’s has been selected as an MMC, the MDT will include specialists from all over the region. The collective knowledge can only benefit patients and staff alike

The Women’s has always been innovative in conducting research to improve women’s health. The Midwifery Research Unit was the first of its kind in the country and conducted a wide variety of research in childbirth. LWH protocols are used in maternity units across the country and are a point of reference for setting protocols in many such units.

As a teaching hospital, LWH is a centre of excellence in the provision of undergraduate and postgraduate medical education and training. According to its own website LWH has “an extremely active multidisciplinary research programme that includes research into maternity studies, gynaecology studies, fertility studies, genetics, oncology and neonatal studies” (LWH 2024d).

The wide range of services available at LWH, makes it ideal to advance research and conduct large-scale clinical trials.

That its location, one mile from an acute hospital site, makes it difficult to recruit and retain staff is hard to believe in view of the fact that it has its full complement of midwives and clinical staff, many of whom have been there for several years. What could have a negative impact on recruitment is more likely to be the 9-year threat to reconfigure services at the Women’s and the lack of certainty of its future.

RISK 05

Women receiving care from women’s hospital services, their families and the staff delivering care, may be more at risk of psychological harm due to the current configuration of services.

They state: There is a risk that pre-existing levels of psychological harm and stress could be exacerbated for women, their families and staff, by the suboptimal way services are currently organised.

There is evidence that 4-5% of women develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) every year after giving birth and high numbers of staff working in gynaecology and maternity services report work-related trauma and symptoms of PTSD.

Delays and workarounds in care can have a negative impact on clinical outcomes, quality of care and patient experience which could create or compound psychological trauma for women, their families and staff.

For the last 14 years NHS staff have been underpaid, overworked and undervalued, conditions that were exacerbated by the pandemic and still continue. The Ockenden review highlighted these issues up and down the country, so psychological problems are not exclusive to the Women’s Hospital.

In a time of increased misogyny, violence towards women and austerity policies that disproportionately affect women, LWH is seen by all women of all ethnicities, who use the services, as a safe place for women.

Liverpool Women’s Hospital is situated in a quiet, landscaped and safe environment. Within the hospital grounds, there is a memorial garden that offers a private space for bereaved families. Another garden was opened in 2016, “The Garden of Hope and Serenity”.

“The idea for this garden came from our gynaecology nursing team who recognised that women and families visiting our Emergency Department at times would benefit from an area away from but adjacent to the department to have time to reflect on conversations with staff and have space and an area of calm to process their thoughts and feelings” (Allison Edis, Deputy Director of Nursing and Midwifery, in 2016, cited in Liverpool Women’s Hospital. 2024e).

There is a wealth of literature that confirms the importance of trees and gardens for patient recovery. A much-cited study by environmental psychologist Roger Ulrich was the first to use the standards of modern medical research to demonstrate that gazing at a garden can sometimes speed healing from surgery, infections and other ailments. It has been proven that just looking at views dominated by trees, flowers or water for a few minutes can reduce levels of anxiety, anger, stress and pain. This can allow other treatments to help healing and induce relaxation that can be measured in physiological changes in blood pressure, muscle tension brain and heart activity (Ulrich 1984).

Studies have shown that loud sounds, disrupted sleep and other stressors can have serious physical consequences and hamper recovery (Ulrich 1991).

Henry Marsh, the celebrated neurosurgeon has stated:

“…these big hospitals are horrible places really, the very last thing you get in an English hospital is peace, rest or quiet which are the very things you need the most”. He goes on to say that the garden he created at St. George’s Hospital “is probably the thing I am most proud of” (The Observer, 2017).

Although the Women’s is situated in a fairly central location it is protected from the sounds and pollution of traffic. There is substantial evidence on the adverse effects of air pollution on different pregnancy outcomes and infant health, including lower birth weight, neonatal jaundice, fetal death, maternal anaemia and other adverse outcomes (Rani and Dhok, 2023).

In the face of all the evidence of the harmful effects of air traffic pollutants on neonates, it is inconceivable that the environmental effects of relocating LWH to either of the acute hospital sites, both situated in the most traffic-dense areas of the city, have not been considered.

Summary

The Case for Change presented to the ICB on the 9th of October 2024 is weak and relies on data gathered before the many improvements at LWH and listed on pages 43 and 44.

The most contentious of the risks that they present focuses on transfers for critical care. On page 7, they state that between 2018 – 2022 there were 69 transfers for critical care, that is, 17 a year. They don’t mention that there was a pandemic during this period, nor do they give figures of transfers between RLH and AUH over the same period (no one is suggesting moving AUH to RUH).

Page 7-8 says that there were 73 serious clinical incidents in gynaecology and maternity services in the period of 2018 -2022. In a clinical review of these incidents, isolation of women’s services from other hospital services was found to be a causal factor in 19 of these incidents and 7 of the 19 involved a transfer for critical care. That is 2 transfers a year. How does it make clinical or financial sense to move a hospital to deal with 2 transfers a year?

Page 8 states there are around 220 ambulance transfers between LWH and either the Royal Liverpool or Aintree hospitals a year, stating that Category 1 or Category 2 made up around half of these transfers. They do not say how many were Category 1 or how many adverse effects there were. They do not make clear if any of these transfers were repatriation transfers.

Page 8 also refers to 148 clinical incidents from July 2022 to March 2024 caused in full or part by women’s services being provided on an isolated site. They do not state if these incidents were in a red, amber or green category. Previous clinical incidents cited in Board papers described one clinical incident as due to there not being a fridge to store breast milk. They do not state if any of these incidents involved transfers.

Page 8 also states that women needing critical care transfer or presenting in Emergency Departments whilst pregnant are more likely to be from ethnic minority groups and socially deprived backgrounds. Where is the evidence that they make up the number of transfers from LWH for critical care?

Page 107 states that the organisation of gynaecology and maternity services in Liverpool has created a significant gender inequality. How is the inequality caused by the organisation and would reorganisation decrease or increase the inequality? They say that this puts women using these services at a disadvantage when compared with people using these services in other parts of the country and men and women using services at other hospitals in Liverpool. Where is the evidence to support this? They go on to state that the demographic profile of women using these services compounds and increases those disadvantages. Where is the evidence? The demographic profile would remain the same if LWH relocated. Where is the evidence that BAME and deprived communities have better treatment at the Royal and Aintree than at LWH?

Page 63 on maternal mortality at LWH is in line with national rates. But LWH intake has more BAME and more deprivation. These factors increase maternal mortality so LWH achieving the national rate means it is doing well. On page 8 paragraph 2.18 they strengthen this argument by reference to MBRACE re impact of deprivation, Black, Asian, severe and multiple deprivation.

Page 94 section 4.4 states that staff at LWH are exposed to events that can trigger the development of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). All health care staff working in the acute setting are exposed to traumatic events. How can relocation prevent this? There are no comparative data from other Trusts about levels of referrals to a trauma-based psychology service. Other factors causing stress among staff could be bullying, overwork, pay, and not being listened to. In LWH Board papers (October 2024), a staff survey showed that 49% of staff feeling negative about their work stated they felt overworked. How is psychological harm to families and patients measured? What about the psychological harm from moving out of L8 and the negative impact on BAME and deprived communities? L8 is home to many BAME women who are reluctant to use public transport due to racial harassment. Relocation to either of the 2 acute sites would put them at risk of harm, both physical and psychological if they were forced to travel on public transport. Has this been addressed?

Page 98 quotes the Royal College of Midwives Maternity Services Report, on a 78% increase in birth to mothers over the age of 40, this in the years 2001 to 2014. The Case for Change does not state any adverse effects, only a need for an increase of resources. Older women may have more risks but this does not equate to high risks. These women will be monitored more closely but if the mother-to-be is healthy then pregnancy will be straightforward (Knight, M.2016). Those with more complex needs will be monitored in the same way as other expectant women, regardless of age, in the many specialised clinics at the Women’s. Re-location will not affect this.

Conclusion

The Case for Change presented to the ICB on 9th October, did not provide any proposals or solutions, it focused on adult maternity and gynaecology hospital services and did not include neonatology. (newborn babies)

It held public engagement sessions to gain feedback from the community. How can a public engagement on such an important topic be held without specifying what the change would be?

How are the public meant to decide on a change without knowing the alternatives?

It is also inconceivable to discuss a change in maternity services without including neonatology. What are the consequences of change for the babies?

When changes to maternity and gynaecology services were first discussed in 2015 the conclusion of LCCG was to build a new hospital adjacent to the new Royal Hospital and connected by a link bridge. This did not materialise. CCGs were closed down following the Health and Care Act of 2022 and ICSs were established and managed by ICBs.The Cheshire and Merseyside ICB has repeatedly stated that there are no funds available to build a new hospital unless it applies the previous government’s definition of a new hospital which could be:

- A whole new hospital on a new or current site

- A major new clinical building or wing of an existing building

- A major refurbishment and alteration of an existing hospital.

As the ICB is focusing on a change in the delivery of maternity and gynaecology hospital services, the reality could be that they are delivered in a wing of one of the existing acute hospitals. The site of the new Royal does not have sufficient space to accommodate the range of services available at LWH at Crown Street, unless it moves some existing services from its current site. The land where the old hospital stood is earmarked for the development of an academic health sciences campus.

Similarly, at Aintree Hospital space is not available unless it moves some services to other areas. Neither solution would provide all services that their case for change deems necessary to comply with standards of co-location of services. They could even be considering 2 small units, one at each site. This would disperse services and the whole ethos of a special hospital for women would be lost. Both acute hospitals are in areas of heavy traffic and parking facilities are inadequate at both sites.

The Case for Change focuses on the safety of services at the Crown Street site. A Care and Quality Commission (CQC) review carried out on 15th January 2024 cited some safety concerns in maternity mostly to do with staffing levels, updates in training, record keeping and staff feeling undervalued, and not respected or supported by management. None of the issues mentioned the site being isolated. Improvements were made and a subsequent unannounced inspection by the CCG gave a rating of good. The recent maternity scandals have all been in co-located hospitals. The maternity services are under-funded and this, with undervalued and underpaid staff have contributed to the tragic events reported across the country together with the non-prioritisation of women in general hospitals.

The Cheshire and Merseyside ICB has a deficit of £150 million. Closing hospitals and reducing bed numbers is a standard response to financial problems imposed by government. Is the Women’s the first of Liverpool’s specialist hospitals to be under threat? We have been told for many years that Liverpool has too many hospitals. The people of Merseyside and Cheshire are fortunate to have so many centres of excellence in their area. This should be a cause of celebration not looked upon as detrimental.

We can only speculate on the ICBs intentions in the absence of any proposals. Are they moving towards the centralisation of services as has been the recent trend? An evaluation of centralising hospital services in Denmark, found that it did not always improve the quality of care (Christiansen, 2012

All maternity units nationally are under-funded, the maternity tariff is inadequate as is Birthrate- plus as a tool to calculate the number of staff needed to meet clinical needs. Staff continue to feel overworked. To improve maternity and gynaecology services nationally, bursaries should be provided for nursing and midwifery students and university programmes for midwifery should be better staffed and funded. Changes need to be made to doctors’ training so they gain more general experience and not concentrate on specialities. Enhanced training for all healthcare professionals in managing women’s health issues and conditions should be provided. Re-location will not solve this. In Cheshire and Merseyside, adequate funding, improvements to workforce training issues, providing emergency obstetrics and gynaecology services at A&E departments at the acute hospitals will all improve quality of care of women in the area. No closure, no privatisation, no cuts, no merger, reorganise the funding structures not the hospital. Our babies, mothers and sick women deserve the very best. These are the changes needed, not the re-location of LWH.

In the event of moving women’s health services from Crown Street, what will become of the building? The ICB has repeatedly stated that it will be used for NHS services: for example, they have considered the Crown Street site being used for out- patients and day case procedures. The question is who will provide these services when they are put out for tender? Will we see Spire Hospital providing NHS funded elective surgery or Spa Medica providing ophthalmology services? That would not sit well with the people of Liverpool.

We remind the ICB once again of the significant investment of the NHS in LWH as a considered effort by the then Dean of Liverpool, to invest in the L8 area through his Project Rosemary following the Toxteth uprising. LWH is a much-loved hospital dedicated to the care of the women and babies of Liverpool and surrounding areas and should remain so.

References

REFERENCES

Adams, T. and Marsh, H. (2017) The Mind-Matter Problem Is Not a Problem for Me, Mind Is Matter. The Observer Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jul/16/henry-marsh-mind-matter-not-a-problem-interview-neurosurgeon-admissions (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

British Medical Association (2024) Outsourced: the role of the independent sector in the NHS Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/media/fy3czsaf/bma-nhs-outsourcing-report-september-2024.pdf Last Accessed 14/12/2024).

Care and Quality Commission (2024) Liverpool Women’s Hospital, January 2024 updated February 2024 Available at:) Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Centre for Health and Public Interest (2014) Patient safety in private hospitals – the known and unknown risks Available at Patient Safety in Private Hospitals — Centre for Health and the Public Interest (Last Accessed 14/12/2024).

Christiansen, T. (2012) Ten years of structural change reforms in Danish healthcare Health Policy 106 (2) pp114-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.03.019

Cleghorn, E. (2021) Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson Publishers

Dusenbery, M . (2019) Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed and Sick New York: HarperOne

Griffith, P., Turner, L, Lown, J. and Sanders, J. (2023) Evidence on the use of Birthrate Plus to guide staffing in maternity – A systematic scoping review Women and Birth Vol.37, Issue 2, pp317-324 Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1871519223003062?via%3Dihub

Hatherley (2022) Hormonal, emotional and irrational: Is it really the case that women’s health is taken less seriously than men’s?

Health and Social Care Act (2012) (Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/contents/enacted (Last Accessed: 17/11/2024).

Intensive Care Society/ Faculty of Intensive care medicine (2013) Core Standards for Intensive Care Units 2013 Available at: https://ics.ac.uk/resource/core-standards-for-icus.html (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Intensive Care Society/ Faculty of Intensive care medicine (2022) Guidelines for the Provision of Intensive care Services Available at https://ficm.ac.uk/sites/ficm/files/documents/2022-07/GPICS%20V2.1%20%282%29.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Kings Fund, The (2021) Is the NHS Being Privatised? Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/big-election-questions-nhs-privatised (Last accessed 12/12/2024).

Knight, M. (2018) Pregnancy complications in older women British Journal of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14269

Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group (2017) Review of Services Provided by Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust Available At: https://www.nesenate.nhs.uk/media/case%20studies/cs8/NE-Clinical-Senate-Liverpool-Womens-Hospital-Final-Report-website.pdf (Last Accessed 14/11/2024)

Liverpool Women’s Hospital (2024a) Liverpool Women’s Maternal Medicine Centre Available at: https://www.liverpoolwomens.nhs.uk/health-professionals/liverpool-women-s-maternal-medicine-centre/ (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Liverpool Women’s Hospital (2024b) Current research Programmes Available at: https://liverpoolwomens.nhs.uk/our-services/research/current-research-programmes/ (Last Accesses 14/12/2024)

Liverpool Women’s Hospital (2024c) New garden offers hope and serenity at Women’s Hospital Available at: https://www.liverpoolwomens.nhs.uk/news/new-garden-offers-hope-and-serenity-at-womens-hospital/ (Last Accessed 14/12/ 2024)

Liverpool Women’s Hospital Foundation Trust Board of Directors (2024) Papers of the Board meeting held 10 October 2024 Available at: https://www.liverpoolwomens.nhs.uk/media/5657/lwh-board-of-directors-meeting-pack-10-october-2024.pdf (Last Accessed 15/12/2024)

Modi, N. (2022) Closing the gender gap: the importance of a women’s health strategy. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/closing-the-gender-health-gap-the-importance-of-a-women-s-health-strategy (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Naylor, Sir R. (2017) NHS property and Estates: Why the estate matters for patients (The Naylor Review) Gov.UK Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-property-and-estates-naylor-review (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

NHS Cheshire and Merseyside ICB (2023) Liverpool Clinical Services Review (January 2023) Available at: https://www.cheshireandmerseyside.nhs.uk/media/vz2na242/cm-icb-board-public-260123.pdf (Last accessed 14/11/2024).

NHS Cheshire and Merseyside Integrated Care Board (2024) Meeting of the Board of NHS Cheshire and Merseyside, 09 October, 2024 Gynaecology and Maternity Hospitals Services in Liverpool – Case for Change p7, 2.15 Available at: https://www.cheshireandmerseyside.nhs.uk/media/zbgatbev/board-meeting-pack-public-october2024.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

NHS England (2024) Adult Critical Care Transfer Services Specification Engagement Report Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ACCTS-Service-Specification-Engagement-Report.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

NHS England (2014) NHS Five Year Forward View Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024).

Northern England Clinical Senate (2017) Review of Services Provided by Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust p17, 6.2.9 and 6.3 Available at: https://www.nesenate.nhs.uk/media/case%20studies/cs8/NE-Clinical-Senate-Liverpool-Womens-Hospital-Final-Report-website.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Ockenden, D. (2022) Ockenden review of maternity services at Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust (web accessible version) Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/624332fe8fa8f527744f0615/Final-Ockenden-Report-web-accessible.pdf.

Rani, P., and Dhok, A. (2023) Effects of Pollution on Pregnancy and Infants Cureus Vol.15 (1) e33906. DOI 10.7759/cureus.33906 Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9937639/pdf/cureus-0015-00000033906.pdf

Royal College of Anaesthetists (2018) The care of the critically ill woman in childbirth; enhanced maternal care 2018 Available at: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2019-09/EMC-Guidelines2018.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Royal College of Midwives (2023) State of Maternity Services Report 2015 Available at: https://rcm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/england-soms-2023.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Save Liverpool Women’s Hospital Campaign/Keep Our NHS Public Merseyside (2017) Response to the CCG’s Review of Women’s and Neonatal Services regarding the clinical case for change Available at: https://www.labournet.net/other/1612/clinical1.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

South East Clinical Senate (2024) The Clinical Co-Dependencies of Acute Hospital Services: Summary of what to find in the main report Available at: https://secsenate.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/The-Clinical-Co-Dependencies-of-Acute-Hospital-Services-Final.-Summary-of-What-to-Find-in-the-Main-Report.pdf (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Sundari, R. (2020) Making pharmaceutical research and regulation work for women British Medical Journal (Online) Vol.371, p1-5 Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27239697

Taylor, J. (2015) EXCLUSIVE: Liverpool Women’s Hospital could close, city’s top NHS boss admits Liverpool Echo15 March 2015 Available at: https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/exclusive-liverpool-womens-hospital-could-9357098 (Last accessed 14/11/24)

Toal, R. (2024) Endometriosis patients being failed and feel dismissed Manchester Metropolitan University Available at: https://www.mmu.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/story/endometriosis-patients-being-failed-and-feel-dismissed-new-study-shows (Last Accessed 14/11/2024)

Ulrich, R.S. (1984) View from a window may influence recovery from surgery Science Vol.224 (4647), pp420-421. Available at: https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/science.6143402?casa_token=mZv2Fj8jQJUAAAAA:5zcOamBue4qUg3H7IxOGeVb3gYIiRPVhTFpdp3Euh9s6TTOjSzLp0TS8q_5Ko322c5PHwdSgNdmw (Last Accessed 14/12/2024)

Ulrich, R.S. (1991) Stress Recovery During Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments Journal of Environmental Psychology Vol.11, pp201-230 Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert-Simons-2/publication/222484914_Stress_Recovery_During_Exposure_to_Natural_and_Urban_Environments_Journal_of_Environmental_Psychology_11_201-230/links/5d669ed2299bf11adf29729c/Stress-Recovery-During-Exposure-to-Natural-and-Urban-Environments-Journal-of-Environmental-Psychology-11-201-230.pdf (Last accessed 14/12/2024)

Wellbeing of Women (2024) “Just a period” Available at: https://www.wellbeingofwomen.org.uk/what-we-do/campaigns/just-a-period/ (Last accessed 14/12/2024)